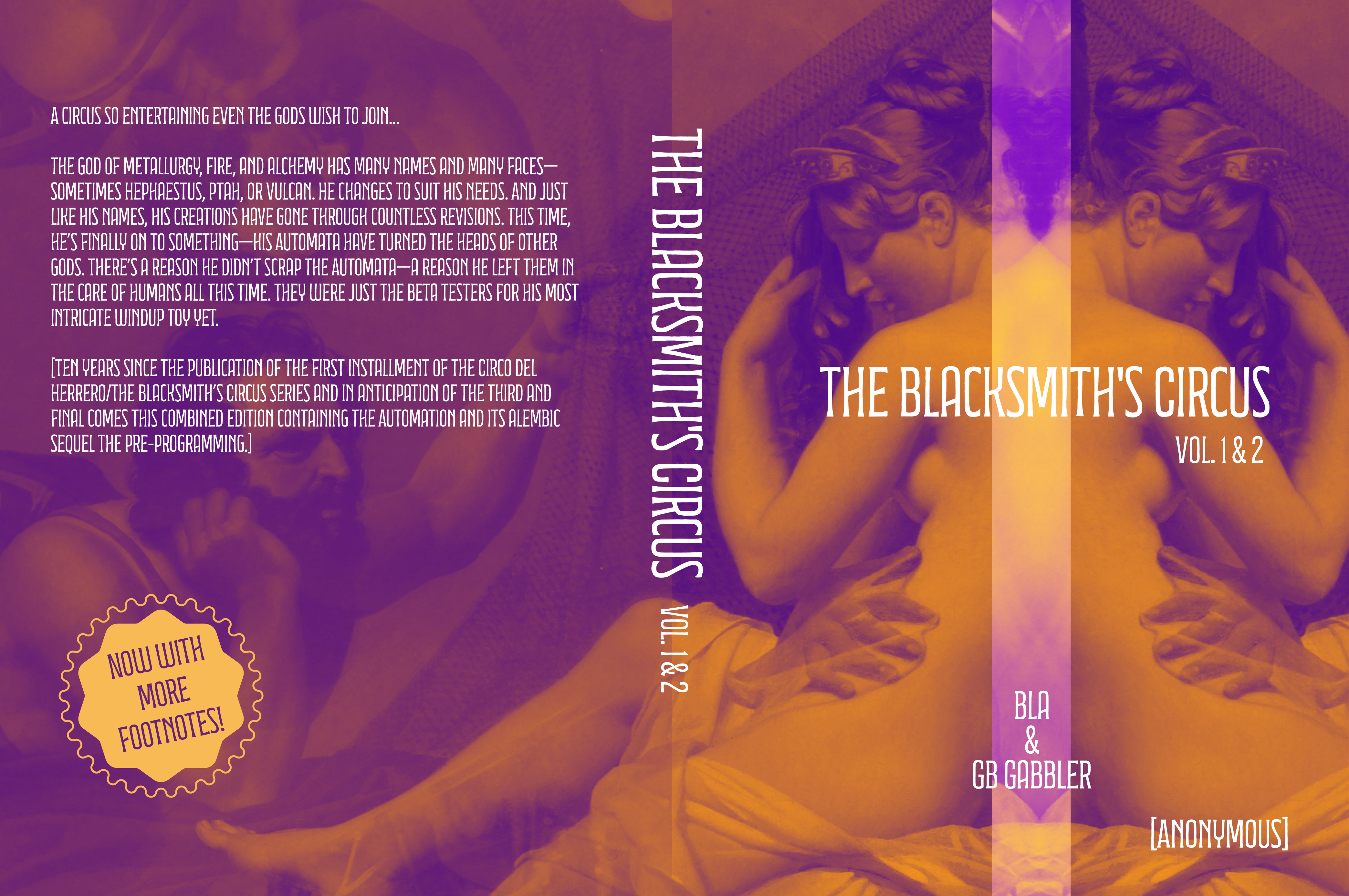

Celebrating 10 years since the publication of The Automation, comes a combined edition — married until their third arrives.

[a website for the Editor and Narrator of the Circo del Herrero series]

Celebrating 10 years since the publication of The Automation, comes a combined edition — married until their third arrives.

In the Egyptian mummification process, all organs were removed and placed in jars, bar the heart. The heart – considered to be the centre of the person’s self, their whole being, their intelligence, their soul – was left in place to be judged by the gods. In the underworld, it was weighed against a feather to see if the person had lived a virtuous life. If it did not make the scales tip, the person was granted entry to the afterlife. If the heart proved heavier than the feather, the goddess Ammit – part lion, part hippopotamus, with the head and teeth of a crocodile – would eat it.

In the mortuary, on the lower ground floor of St Thomas’ Hospital, on the South Bank of the Thames, a heart is placed on scales and the result shouted across the room to be recorded on a whiteboard in fading pen. Its weight is determined to be healthy or unhealthy 0 here you are judged only on what is known and seen by naked eye or microscope. It is not for these people to rule on how you lived, but how you died, on the balance of probability.

– Hayley Campbell, All The Living And The Dead

“Good literature is often evocative, using imagery and metaphor to stimulate the imagination rather than prosaic description to satisfy the intellect. This has the great advantage of enabling the reader to enter creatively into the experience of the author, and more than outweighs the resultant imprecision and possible misunderstanding. But of course imagery by its very nature cannot be pressed too far. Old Testament descriptions of death are often imaginative and evocative rather than prosaic and specific. This allows us to understand the ancient Israelites’ attitudes to death more than their beliefs about it. Nevertheless, the imagery and metaphor used inevitably reflect certain beliefs, and it is useful to attempt to trace these.

“Good literature is often evocative, using imagery and metaphor to stimulate the imagination rather than prosaic description to satisfy the intellect. This has the great advantage of enabling the reader to enter creatively into the experience of the author, and more than outweighs the resultant imprecision and possible misunderstanding. But of course imagery by its very nature cannot be pressed too far. Old Testament descriptions of death are often imaginative and evocative rather than prosaic and specific. This allows us to understand the ancient Israelites’ attitudes to death more than their beliefs about it. Nevertheless, the imagery and metaphor used inevitably reflect certain beliefs, and it is useful to attempt to trace these.

Further, in all human life, concepts from the cultural background may be taken up and used without acceptance of their underlying ideology. Today people from all walks of life talk of an Achilles’ heel, Cupid’s arrows, or the fates, or use adjectives like ‘titanic’ and ‘promethean,’ without believing the Greek mythology which underlies these terms. Christians have often celebrated Halloween as a harmless folk festival, without worrying about its roots. Thus Israel’s use of certain terms need not imply acceptance of the mythology associated with [it] by other peoples. Neighbouring cultures used terms like death, pestilence and plagues to represent deities, but the Hebrew usage does not necessarily echo this.” – pg 25

“The most important Hebrew term for the underworld is clearly…‘Sheol’… for several reasons: (a) It is the most frequent, occurring sixty-six times. (b) It always occurs without the definite article (‘the’), which implies that it is a proper name. (c) It always means the realm of the dead located deep in the earth, unlike other terms which can mean both ‘pit’ and ‘underworld.’” -pg 70

Shades of Sheol: Death and Afterlife in the Old Testament by Philip S. Johnston