Both volumes 1 and 2 are currently free.

While you might know volume 1 is permafree (fine, compare us to a drug dealer), we need you to now volume 2 is free for a limited time as a Kindle ebook here.

[a website for the Editor and Narrator of the Circo del Herrero series]

Both volumes 1 and 2 are currently free.

While you might know volume 1 is permafree (fine, compare us to a drug dealer), we need you to now volume 2 is free for a limited time as a Kindle ebook here.

Edith set out to create an entirely new version only of Thomas Bulfinch’s first mythology book, The Age of Fable, which had contained Greek, Roman, and Norse myths. Bulfinch, who had received his education in classics at the Boston Latin School and at Harvard, had died in 1867, the year Edith was born. He had been a Boston bank clerk when he had published The Age of Fable, which was subsequently revised many times; the title Bulfinch’s Mythology was generally used for later editions of the work, which included not only the myths of the first volume but also Bulfinch’s later works The Age of Chivalry and Legends of Charlemagne, initially published in 1858 and 18631 respectively. Edith’s model was confined to The Age of Fable since she originally intended to include only the Greek and Roman myths, with the brief section on Norse mythology a slightly later addition.

…

The project’s attraction lay in its subject’s wide appeal: mythology was an aspect of ancient Greek culture with which a potentially large reading audience hoped to become more familiar. As Bulfinch’s biographer Marie Sally Cleary has pointed out, one reason for the success of The Age of Fable was the existence of a public cager to better understand

mythological references in Western art and literature. By writing a new mythology book, Edith could tap into the primary means by which readers became curious about ancient Greece. Bulfinch had aided his readers’ quest for greater appreciation of art and literature by including quotations from poems that alluded to a myth before his telling of each story, something that Edith also originally intended to do in her volume. Instead, she commented on the sources for each story, identifying the ancient authors from whom she had drawn the tale, a change that indicated the ultimate limits of Bulfinch as her model. As she began work on the book it quickly became apparent that in terms of content she would vary considerably from the earlier author.Edith found Bulfinch’s work readable but felt that the large number of quotations from poetry actually defeated the purpose of making the subject of mythology accessible to readers. Edith’s approach was therefore the opposite of Bulfinch’s. Rather than providing excerpts from the poems inspired by a particular tale, she imagined the reader encountering a reference to a myth in either art or literature and subsequently wishing to read only the story, not other allusions to it. Nevertheless, she was conscious of which mythological tales a potential reader might encounter, causing her to include at least one story that Bulfinch had left out: the tale of Amphitryon, whose wife Alcmena bore a son, the hero Hercules, by Zeus. Finding Bulfinch occasionally old-fashioned, she felt he had omitted the tale, along with the Roman story of Lucretia, because both narratives revolved around tests of a woman’s virtue. Edith, however, initially planned to include both tales, as she felt there were many allusions to both characters in English poetry, though only the story of Amphitryon appeared in Mythology.

She also wanted to arrange the stories differently than Bulfinch, paying more attention to chronology, beginning with what could be identified by authorship as the oldest tales, the ones drawn from the Homeric Hymns and from Hesiod. She also wanted to add more context before each story, explaining “the way the myths may have originated and the way they have developed.” By late 1938, she already envisioned, she told Everitt, “a book a little more grown-up than Bulfinch, but only a little.”

Only in two respects was Bulfinch’s work a definite model. Edith, like Bulfinch, wrote a lengthy section at the beginning of the book describing the attributes of the gods and goddesses and the other lesser divinities. Also, from its inception Everitt felt that Mythology should have illustrations. Ultimately, the publisher commissioned Steele Savage, who had illustrated Sally Benson’s mythology book three years earlier, to create the artwork for Edith’s volume.

Bulfinch’s influence on the content and the length of Edith’s work was limited. For the latter, she turned to Charles Mills Gayley’s Classic Myths as a guide. It was a work with which she was familiar, having told its stories to Dorian and the other Reid children…

As Edith researched Mythology, she compiled lists of the stories she wanted to include. In the first pages of her notebook she listed forty-four stories under the heading “Done,” including the fifteen tales comprising Jason’s quest for the Golden Fleece. She also made notes of stories she had yet to write, organized into “Important,” “Fairly Important,” and “Unimportant:’ Included under the heading “Important” were such myths as Hercules, Perseus, Phaeton, and the legend of Theseus. These were all included in the final volume, but some of the tales that she listed as “Unimportant,” such as the story of King Midas or those of Callisto or Antiope, nevertheless found their way into Mythology in the sections titled “The Less Important Myths” and “Brief Myths.” She found other ways to include stories that she had labeled “Fairly Important” in the book. As Edith organized her material, she found that the stories of Ceyx and Alcyone, and Pygmalion and Galatea, rounded out the section titled “Eight Brief Tales of Lovers.” This section also included myths she had listed as “important,” including Pyramis and Thisbe and the story of Orpheus and Eurydice. She also made lists of characters or mythological creatures she wanted to research, such as Orion, Astraea, and the Cranes of lbycus. When she finished writing a story, she crossed it off her list. Concern about the length of the mythology book, however, meant that some myths had to be excluded. Edith was always cautious about the length of Mythology, feeling too large a volume would defeat the purpose of making the subject accessible.

…

Edith found the Norse portion of the volume the most challenging to write. Initially, she had not planned to include it at all. Norse mythology was not a subject with which she felt familiar, having gained her knowledge of it largely through listening to Wagnerian opera. She had, however, likely read the Germania of the Roman historian Tacitus, which described the rituals used in worshipping the Norse gods. Both Bulfinch and Gayley had included Norse mythology in their own books, one reason why Edith may have at last added it to hers. The time period in which she wrote Mythology suggests another. Interest in Norse mythology revived with the rise of Nazism in Germany, making it a potentially contentious subject on which to write. A section on Norse mythology, however, would help readers to at least understand some of the Third Reich’s symbolism.

Edith, in her introduction to the section on Norse mythology, drew a sharp dichotomy between the culture that had produced these tales and Christianity. She painted a picture of the early Christians as almost completely successful in their efforts to stamp out the literature of the pre-Christian Norse on the European continent. The result of this struggle, Edith argued, was that Christians drew no inspiration from Norse culture. The Nazis might use it for their symbolism, but they were drawing on a cultural tradition completely different from Christianity.

…

Brevity, however, was not the only criticism offered of the section of Norse myths. Padraic Colum, the folklorist and poet of the nationalist Irish Renaissance, who taught comparative literature at Columbia University, was more critical of it in his review published in an August issue of the Saturday Review of Literature. Colum had had no formal training in the classics but was nevertheless drawn to the ancient world. he had published several books of Greek myths for a juvenile audience and a book of Norse mythology, The Children of Odin, which had appeared in 1920. Colum had considerable success as a children’s writer and Edith was certainly aware of his work, which she referred to in her own notes for Mythology.

Colum was critical of Edith’s introduction to the section of Norse mythology, calling it “wrong-headed in a way surprising to find in the work of a scholar such as Miss Hamilton.” He was dismayed that Edith had described the English as a primarily Teutonic people, a claim he disputed, along with Edith’s use of Norse and Teutonic as virtual synonyms. In Edith’s conception of “Teutonic,” Colum saw, correctly, the influence of Charles Kingsley, who had briefly referred to both the eddas and the sagas as well as to Beowulf in his introduction to The Heroes, without distinguishing among the cultures that produced them. Colum, probably also reacting to the rise of Nazis and their racial theories, opposed Kingsley’s conception of “muscular Christianity”: firm belief in both Protestantism and the physical and mental superiority of the Teutonic peoples. Moreover, he strongly disagreed with Edith’s assertion that Christians had seen Christianity in conflict with Norse mythology to such an extent that clergy had expended much effort in stamping out the Norse tales. Colum used Ireland as an example of where Christian theology and Norse mythology had coexisted, with the clergy actually preserving Norse literature. Edith, however had been mainly interested in separating Christianity and Norse mythology in Germany itself, where the Nazis were using the Norse literature to create a mythology of their own.

Colum understood the fundamental purpose of Edith’s book: to provide a reference for readers seeking to understand mythological allusions in other works of literature. He praised the volume as a thorough survey of Greek and Roman mythology, singling out especially Edith’s rendition of the story of the maiden Marpessa who, urged by Zeus to choose between her two suitors, Apollo and a mortal named Idas, one of the Argonauts, chose the latter. It was a myth that Edith had labeled “unimportant” in her own notes for the manuscript, and it appeared in “Brief Myths Arranged Alphabetically” at the end of the book. Similarly, Colum welcomed Edith’s clarification of another myth that involved violence against women, the story of Procne and Philomela, daughters of King Erechtbeus of Athens, who were both transformed into birds to escape the vengeance of Procne’s husband, Tereus. In his anger, Tereus had cut out Philomela’s tongue, but she had been nevertheless described by Roman and later English poets as the nightingale. In the Greek story, the gods had turned Philomela into a swallow, a bird that cannot sing, while Procne had become the nightingale.

Mythology proved to be Edith’s most enduring book despite the contemporary references in some of the stories. Edith’s opposition to fascism was particularly noticeable in her telling of the tale of Prometheus, chained to a mountainside in the Caucasus for giving humans the gift of fire and for refusing to reveal the name of the mother who would bear a son who would challenge Zeus. For these, Prometheus was viewed as the friend of humanity and a symbol of free thought as opposed to tyranny.88 This had been evident to her when she had translated the Prometheus Bound of Aeschylus but was more pronounced in Mythology, since the Nazis made use of Prometheus as an ”Aryan,” helping to bring forth Western civilization. Edith therefore constructed a Prometheus who stood for spiritual freedom, one who “has stood through all the centuries, from Greek days to our own, as that of the great rebel against injustice and the authority of power.” She would echo similar sentiments in her speech in Athens in 1957 as she received her honorary citizenship to the city before a performance of her translation of Prometheus Bound.

…

More importantly for Edith, Edward Caird had compared the moral impacts of the deaths of Socrates and Jesus.

Edith saw Socrates and Jesus as sharing the same method of teaching through the example of their own lives. Neither told individuals what to believe but instead urged others to seek the truth as they did. Both sought to help individuals do so, not by retiring from society but by being active in its daily life. Socrates flourished in fifth century BCE Athens, whose citizens were eager to engage in philosophical discussion with him, even as war began between Athens and Sparta. Edith was quick to point out that, in times of war, philosophical discussion, with its exchange of ideas, was even more vital than in times of peace.

Initially, war had not stopped the circulation of ideas on which the Athenians thrived. The staggering length of the Peloponnesian War, which lasted twenty-seven years, and its conclusion in the defeat of Athens however, produced a sea change in the city’s values, the kind of societal moral shift to which Edith was always sensitive. The Athenians sentenced Socrates to death five years after the war’s conclusion. To Edith, the reason for this sentence, corrupting the young through the introduction of new gods, only supported her argument that Socrates’s method had helped lay the groundwork for Christianity. The Olympic gods, she had argued in her introduction to Mythology, had ultimately been unable to fulfill human longing for a divinity who protected humanity and who both stood for and demanded ethical behavior. Socrates, by urging the young of Athens to search for the good, had discarded the official religion of Athens, as belief in “Homer’s jovial, amoral Olympians [was] impossible for any thinking person to take seriously.”

In defeat, however, Athenians treated Socrates with suspicion. He had no fixed dogmas or creeds to substitute for the gods he had discarded. Instead, he offered only a method of questioning, of searching for the good. As Edith explained to Storer a few months before Witness to the Truth was published, “Socrates by temperament and his basic point of view was closer to Christ than anyone else. I believe he is a help to understanding Christ, a stepping-stone to an apprehension of that greatest of all figures.

Throughout Witness to the Truth, Edith offered her readers various solutions to the challenges of maintaining Christian faith. In the book’s third chapter, “How the Gospels Were Written;’ she explained how to approach reading the Gospels, to which various additions had been made over time, including recitations of miracles and messianic predictions. She identified the list of miracles at the end of the Gospel of Mark as one of these later additions, arguing that the “entire passage is on a level immeasurably below the rest of the Gospel” and that as early as the fourth century it was recognized as being a substitute for the original ending of Mark, which had been lost. The persecutions that Mark and other Christians experienced in the first century of the Roman Empire accounted for the Gospel’s messianic statements. But Jesus, Edith argued, was independent of concern for time and place. “If Christ is here for the modern world, it is because he is independent of changes of time and stages of knowledge. Today it is impossible to find a refuge from the evils of the world in an expectation that presently God will intervene to destroy the wicked and exalt the good.” Belief in Jesus’s message, she argued, should not be dependent on the supernatural.

The facts, such as they are, about the god are first that he was beautiful, in an androgynous way, to both men and women. Euripides describes him with “long curls…cascading close over [his] cheeks, most seductively.” Cross-dressing was part of Dionysian worship in some locales. Although he had occasional liaisons with women, like the Cretan princess Ariadne, he is usually portrayed as “detached and unconcerned with sex.” In vase paintings he is never shown “involved in the satyrs sexual shenanigans. He may dance, he may drink, but he is never shown paired with…any of the female companions.

As one of the few Greek gods with a specific following, he had a special relationship to humans. They could evoke him by their dancing, and it was he who “possessed” them in their frenzy. He is, in other words, difficult to separate from the form that his worship took, and this may explain his rage at those who refused to join in his revels, for Dionysus cannot fully exist without his rites. Other gods demanded animal sacrifice, but the sacrifice was an act of obedience or propitiation, not the hallmark of the god himself. Dionysus, in contrast, was not worshipped for ulterior reasons (to increase the crops or win the war) but for the sheer joy of his rite itself. Not only does he demand and instigate; he is the ecstatic experience that, according to Durkheim, defines the sacred and sets it apart from daily life.

So it may make more sense to explain the anthropomorphized persona of the god in terms of his rituals, rather than the other way around. The fact that he is asexual may embody the Greeks’ understanding that collective ecstasy is not fundamentally sexual in nature, in contrast to the imaginings of later Europeans. Besides, men would hardly have stood by while their wives ran off to orgies of a sexual nature; the god’s well-known indifference guarantees their chastity on the mountaintops. The fact that he is sometimes violent may reflect Greek ambivalence toward his rites: On the one hand, for an elite male perspective, the communal ecstasy of underlings (women in this case) is threatening to the entire social order. On the other hand, the god’s potential cruelty serves to help justify each woman’s participation, since the most terrible madness and violence are always inflicted on those who abstain from his worship. The god may have been invented, then, to explain and justify preexisting rites.

If so, the Dionysian rites may have originated in some “nonreligious” practice, assuming that it is even possible to distinguish the “religious” from other aspects of a distant culture….

No doubt the Roman male elite had reason to worry about unsupervised ecstatic gatherings. Their wealth had been gained at sword point, their comforts were provided by slaves, their households managed by women who chafed—much more noisily than their sisters in Greece—against the restrictions imposed by a perpetually male political leadership. Two centuries after the repression of Dionysian worship in Italy, in 19 CE, the Roman authorities cracked down on another “oriental” religion featuring ecstatic rites: the cult of Isis. Again there was a scandal involving the use of a cult for nefarious purposes, though this time the victim was a woman, reportedly tricked by a rejected lover, into having sex with him in the goddess’s temple….

So it is tempting to divide the ancient temperament into a realm of Dionysus and a realm of Yahweh—hedonism and egalitarianism versus hierarch and ward. On the one hand, a willingness to seek delight in the here and now, on the other, a determination to prepare for future danger. A feminine, or androgynous, spirit of playfulness versus the cold principle of patriarchal authority. This is in fact how Robert Graves, Joseph Campbell, and many since them have understood the emergence of a distinctly Western culture: As the triumph of masculinism and militarism over the anarchic traditions of a simpler agrarian age, of the patriarchal “sky-gods” like Yahweh and Zeus over the great goddess and her consorts. The old deities were accessible to all through ritually induced ecstasy. The new gods spoke only through their priests or prophets, and then in terrifying tones of warning and command.

But this entire dichotomy breaks down with the arrival of Jesus, whose followers claimed him as the son of Yahweh. Jesus gave the implacable Yahweh a human face, making him more accessible and forgiving. At the same time, though—and less often noted—Jesus was, or was portrayed by his followers as, a continuation of the quintessentially pagan Dionysus.

Ch. 3

In what has been called “one of the most haunting passages in Western literature,” the Greek historian Plutarch tells the story of how passengers on a Greek merchant ship, sometime during the reign of Tiberius (14-37 BCE), heard a loud cry coming from the island of Paxos. The voice instructed the ship’s pilot to call out, when he sailed past Palodes, “The Great God Pan is dead.” As soon as he did so, the passengers heard, floating back to them from across the waters, “a great cry of lamentation, not of one person, but of many.”

It’s a strange story: one disembodied voice after another issuing from over the water. Early Christian writers seemed only to hear the first voice, which signaled to them the collapse of paganism in the face of nascent Christianity. Pan, the honed god who overlapped Dionysus as a deity of dance and ecstatic states, had to die to make room for the stately and sober Jesus. Only centuries later did Plutarch’s readers full attend to the answering voices of lamentation and begin to grasp what was lost with the rise of monotheism. In a world without Dionysus/Pan/Bacchus/Sabazios, nature would be dead, joy would be postponed to an afterlife, and the forests would no longer ring with the sound of pipes and flutes.

…

The general parallels between Jesus and various pagan gods were laid out long ago by James Frazer in The Golden Bough. Like the Egyptian god Osiris and Attis, who derived from Asia Minor, Jesus was a “dying god,” or victim god, whose death redounded to the benefit of humankind. Dionysus, too, had endured a kind of martyrdom. His divine persecutor was Hera, the matronly consort of Zeus, whose anger stemmed from the fact that it was Zeus who fathered Dionysus with a mortal woman, Semele. Hera ordered the baby Dionysus torn to shred but he was reassembled by his grandmother. Later Hera tracked down the grown Dionysus and afflicted him with the divine madness that caused him to roam the world, spreading viniculture and revelry. In this story, we can discern a theme found in the mythologies of many apparently unrelated cultures: that of the primordial god whose suffering, and often dismemberment, comprise, or are necessary elements of, his gifts to humankind.

The obvious parallel between the Christ story and that of pagan victim gods was a source of great chagrin to second-century Church fathers. Surely their own precious savior god could not have been copied, or plagiarized, from disreputable pagan cults. So they ingeniously explained the parallel as a result of “diabolical mimicry”: Anticipating the arrival of Jesus Christ many centuries later, the pagans had cleverly designed their gods to resemble him. Never mind that this explanation attributed supernatural, almost godlike powers of prophecy to the pagan inventors of Osiris, Attis, and Dionysus.

…In at least one significant respect, Jesus far more resembles Dionysus than Attis. Attis was a fertility god who died and was reborn again each year along with the earth’s vegetation, while Jesus, like Dionysus, was markedly indifferent to the entire business of reproduction. For example, we know that Jewish women in the Old Testament were devastated by infertility. But although Jesus could cure just about anything, to the point of reviving the dead, he is never said to have “cured” a childless woman—a surprising omission if he were somehow derived from a pagan god of fertility.

…

Considering the “popularity of the cult of Dionysus in Palestine” as well as the material evidence from coins, funerary objects, and building ornaments showing that Yahweh and Dionysus were often elided or confused, Smith concluded that “these factors taken together make it incredible that these symbols were meaningless to the Jews who used them. The history of their use shows a persistent association with Yahweh of attributes of the wine god.”

….

Could there have been any actual overlap between the cults of Jesus and Dionysus, or fraternal mixing of the two? In support of that possibility, Timothy Freke and Peter Grandy, in their somewhat sensationalist book The Jesus Mysteries, offer a number of cases, from the second and third centuries, in which Dionysus—who is identified by name—is depicted hanging from a cross.

…

Christian solidarity stemmed in part from Jesus’ sweet and spontaneous form of socialism, but it had a dark, apocalyptic side too. He had preached that the existing social order was soon to give way to the kingdom of heaven, hence the irrelevance of the old social ties of family and tribe. Since the final days were imminent, it was no longer necessary to have children or to even cleave to one’s (unbelieving) spouse or kin—a feature of their religion that “pro-family” Christians in our own time conveniently ignore.

…

But were the fascist rallies of the 1930s really examples of collective ecstasy, akin to Dionysian rituals? And if so, does the threat of uncontrollable violence stain every gathering, every ritual and festivity, in which people experience transcendence and self-loss?

We begin with an important distinction: The mass fascist rallies were not festivals or ecstatic rituals, they were spectacles, designed by a small group of leaders for the edification of the many. Such spectacles have a venerable history, going back at least to the Roman Empire, whose leaders relied on circuses and triumphal marches to keep the citizenry loyal. The medieval Catholic Church used colorful rituals and holiday processions to achieve the same effect, parading statues of saints through the streets, accompanied by gorgeously dressed Church officials. In a mass spectacle, the objects of attention – the marchers or, in the Roman case, chained captive sand exotic animals in cages—are only part of the attraction. Central to the experience is the knowledge that hundreds or thousands of other people are attending the same spectacle—just as, in the age of television, the announcer may solemnly remind us that a billion or so other people are also tuned in to the same soccer came or Academy Awards presentation.

…c

An audience is very different from a crowd, festive or otherwise. In a crowd, people are aware of one another’s presence, and, as Le Bon correctly intuited, sometimes emboldened by their numbers to do things they would never venture on their own. In an audience, by contrast, each individual is, ideally, unaware of other spectators except as a mass. He or she is caught up in the speech, the spectacle, the performance—and often further isolated from fellow spectators by the darkness of the setting and admonitions against talking to one’s neighbors. Fascist spectacles were meant to encourage a sense of solidarity or belonging, but in the way that they were performed, and in the fact they were performed, the reduced whole nations to the status of audience.

-Dancing in the Streets: A History of Collective Joy by Barbara Ehrenreich

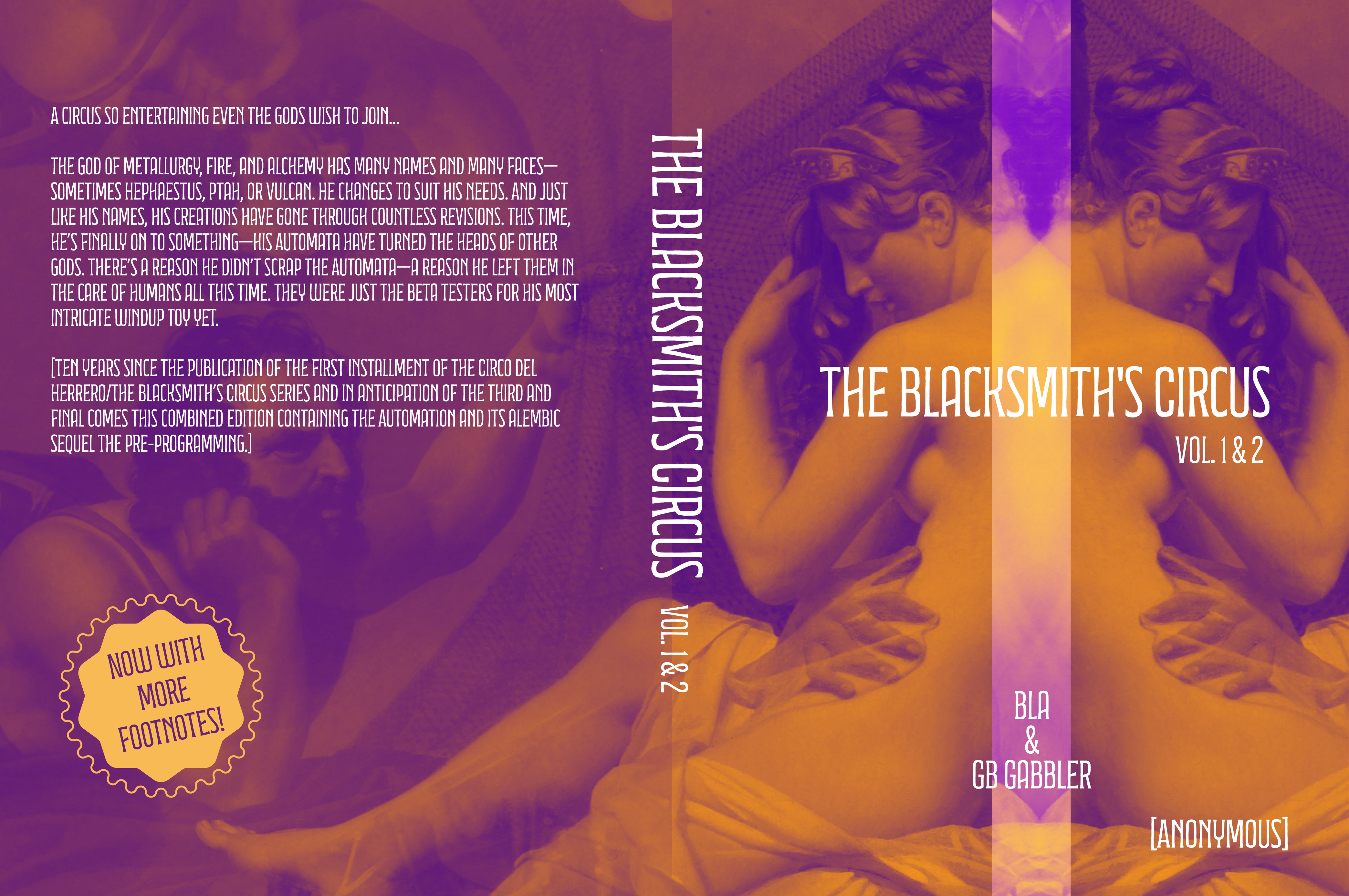

Celebrating 10 years since the publication of The Automation, comes a combined edition — married until their third arrives.

The central problem with Singularity theory is that it is really only attractive to nerds. Vibing with all of humanity across the universe would mean entangling your consciousness with that of every other creep, and if you’re selling that vision and don’t see that as an issue, then it probably means that you’re the creep. Kurzweil’s The Singularity is Near is paternalistic and at times downright lecherous; paradise for me would mean being almost anywhere he’s not. The metaverse has two problems with its sales pitch: the first is that it’s useless; the second is that absolutely nobody wants Facebook to represent their version of forever.

Of course, it’s not like Meta (Facebook’s rebranded parent company) is coming right out and saying, “hey we’re building digital heaven!” Techno-utopianism is (only a little bit) more subtle. They don’t come right out and say they’re saving souls. Instead they say they’re benefitting all of humanity. Facebook wants to connect the world. Google wants to put all knowledge of humanity at your fingertips. Ignore their profit motives, they’re being altruistic!

…

In recent years, a bizarre philosophy has gained traction among silicon valley’s most fervent insiders: effective altruism. The basic gist is that giving is good (holy) and in order to give more one must first earn more. Therefore, obscene profit, even that which is obtained through fraud, is justifiable because it can lead to immense charity. Plenty of capitalists have made similar arguments through the years. Andrew Carnegie built libraries around the country out of a belief in a bizarre form of social darwinism, that men who emerge from deep poverty will evolve the skills to drive industrialism forward. There’s a tendency for the rich to mistake their luck with skill.

But it was the canon of Singularity theory that brought this prosaic philosophy to a new state of perversion: longtermism. If humanity survives, vastly more humans will live in the future than live today or have ever lived in the past. Therefore, it is our obligation to do everything we can to ensure their future prosperity. All inequalities and offenses in the present pale in comparison to the benefit we can achieve at scale to the humans yet to exist. It is for their benefit that we must drive steadfast to the Singularity. We develop technology not for us but for them. We are the benediction of all of the rest of mankind.

Longtermism’s biggest advocates were, unsurprisingly, the most zealous evangelists of web3. They proselytized with these arguments for years and the numbers of their acolytes grew. And the rest of us saw the naked truth, dumbfounded watching, staring into our black mirrors, darkly.

…

Longtermists offered a mind-blowing riposte: who cares about racism today when you’re trying to save billions of lives in the future?

…

Humanity’s demise is a scarier idea than, say, labor displacement. It’s not a coincidence that AI advocates are keeping extinction risk as the preëminent “AI safety” topic in regulators’ minds. It’s something they can easily agree to avoid without any negligible impact in the day-to-day operations of their business: we are not close to the creation of an Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), despite the breathless claims of the Singularity disciples working on the tech. This allows them to distract from and marginalize the real concerns about AI safety: mass unemployment, educational impairment, encoded social injustice, misinformation, and so forth. Singularity theorists get to have it both ways: they can keep moving towards their promised land without interference from those equipped to stop them.

…

Effective altruism, longtermism, techno-optimism, fascism, neoreactionaryism, etc are all just variations on a savior mythology. Each of them says, “there is a threat and we are the victim. But we are also the savior. And we alone can defeat the threat.” (Longtermism at least pays lip service to democracy but refuses to engage with the reality that voters will always choose the issues that affect them now.) Every savior myth also must create an event that proves that salvation has arrived. We shouldn’t be surprised that they’ve simply reinvented Revelations. Silicon Valley hasn’t produced a truly new idea in decades.

…

Technologists believe they are creating a revolution when in reality they are playing right into the hands of a manipulative, mainstream political force. We saw it in 2016 and we learned nothing from that lesson.

Doomsday cults can never admit when they are wrong. Instead, they double down. We failed to make artificial intelligence so we pivoted to artificial life. We failed to make artificial life so now we’re trying to program the messiah. Two months before the Metaverse went belly-up, McKinsey valued it at up to $5 trillion dollars by 2030. And it was without a hint of irony or self-reflection that they pivoted and valued GenAI at up to $4.4 trillion annually. There’s not even a hint of common sense in this analysis.

[Via]