To be fair, Moshfegh has never tried to defend her characters on moral grounds. She intends that they be outsiders, freaks, malcontents. “I let them say what they want,” she told one interviewer. “Usually they’re saying something too honest.” The effect can be powerful. After Eileen casually humiliates a young woman who is visiting her rapist, she reflects, “I suppose I may have been envious. No one had ever tried rape me.” The sentence slices through you like an icicle—the wit of it, the horror, the heartbreak, the audacity of such poor taste—and the pieces melt away before you can decide how it made you feel. In My Year of Rest and Relaxation, the orphaned narrator mentally flicks away her mother’s suicide note by calling it “totally unoriginal.” The quip is devastating not least because there really is something cliché about the grandeur of depression—and there really isn’t a right time to bring it up. If this is what Moshfegh means when she speaks of telling people “the truth they don’t want to hear,” then good: She is well within the remit of all the best fiction, which rightly holds up a sharp pin for our worst angels to dance on.

…

This is all well and good; it has the pleasing shape of radical sentiment without the encumbrance of any actual political commitments. In reality, it is very easy to oppose the banning of a book like Lolita while also pointing out that the author of American Psycho is a sundowning reactionary. But Moshfegh seems to believe that unsettling moral perspectives are better found in novels than in readers. For her, the threat to the novel is posed not by murderous corporations, which are merely window-dressing here, but by a sinister “political agenda” found, like all political agendas, in the swarming tweets of strangers. The substance of that agenda is easy to guess—social justice, both real and imagined—but what Moshfegh really means is what most successful artists mean when they speak vaguely about the value of art: the absolute indignity of being told what to do.

Beneath all the bluster, the only political enemies Moshfegh openly acknowledges are commercialism and agitprop—that is, the desecration of art by money and power. The narrator of My Year of Rest and Relaxation speaks with uncharacteristic reverence of the “ineffable quality of art as a sacred human ritual” and laments the art world’s enslavement to “political trends and the persuasions of capitalism.”

..

This is why we all shit: to be renewed. Everything else—money, political ideology, institutions of all kinds—is a distraction from the fundamental unity of shit and spirit. “We are spiritual and we’re human poop machines,” Moshfegh says. “We are divine and we are disgusting. We’re having these incredible lives and then we’re going to be dead and rot in the ground.”

…

For all its technical mastery, there remains something deeply juvenile about Moshfegh’s fiction, colored in with an existential discomfort that the author has not updated since childhood.

…

Like the art-touching scene at the end of My Year of Rest and Relaxation, Ina’s miracle is a clear allegory for the very novel it concludes—all the way down to the motif of the hand, which might as well be holding a pen. Moshfegh describes her writing process as an ecstatic experience of “channeling a voice,” and she has often expressed a desire to “be pure and real and make whatever is coming to me from God.” The epigraph to Lapvona, “I feel stupid when I pray,” is taken from a Demi Lovato song about feeling abandoned by God. But the phrase also recalls Moshfegh herself, who imagines that her “destiny” is to reach into readers and transmit the divine. “My mind is so dumb when I write,” she told an early interviewer. “I just write down what the voice has to say.” In other words, there’s a reason God isn’t listening: He’s busy praying to people like Moshfegh.

…

That’s a nice thought. It must be convenient to believe in a God whose theological features consist in giving you divine permission to write whatever you want. But even with all the authority of heaven behind her, Moshfegh would rather preach righteousness to an empty chapel than break bread with the weak and the blind. This is the problem with writing to wake people up: Your ideal reader is inevitably asleep. Even if such readers exist, there is no reason to write books for them—not because novels are for the elite but because the first assumption of every novel must be that the reader will infinitely exceed it. Fear of the reader, not of God, is the beginning of literature. Deep down, Moshfegh knows this. “If I didn’t like what I read, I could throw the book across the room. I could burn it in my fireplace. I could rip out the pages and use them to blow my nose,” observes the widow of Death in Her Hands. Yet the novelist continues to write as if her readers are fundamentally beneath her; as if they, unlike her, have never stopped to consider that the world may be bullshit; as if they must be steered, tricked, or cajoled into knowledge by those whom the universe has seen fit to appoint as their shepherds.

[Via]

[The Author does not know if they agree with the statement “Fear of the reader, not of God, is the beginning of literature” or this review at large. Interesting perspective, though.]

Contained in these briefest of sketches, however, are important keys to understanding the full intent of Haraway’s ironic myth. The Manifesto calls on SF in a number of ways. First, and crucially, looking to SF becomes a way of foregrounding and talking about the mythic elements of technoscience. The Manifesto is centrally concerned with a reconstruction of socialist-feminist politics “in the belly of the monster” – a drive that requires a “theory and practice addressed to the social relations of science and technology, including crucially the systems of myth and meanings structuring our imaginations” (Haraway 1991a: 163). For Haraway, SF is a useful tool for foregrounding such “systems of myth;’ especially if we export our SF reading practices to science and see both as stories about science.

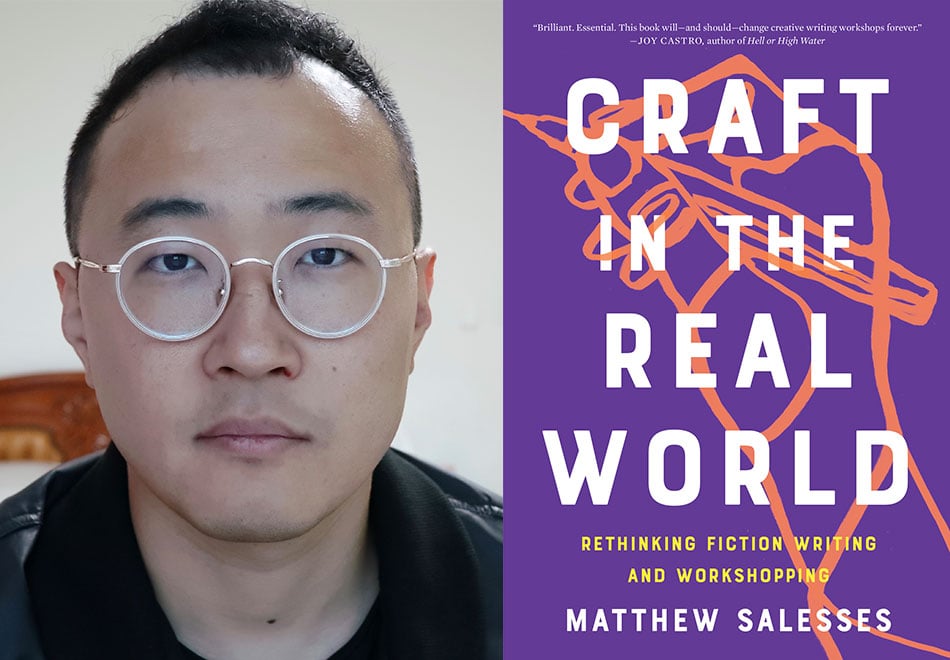

Contained in these briefest of sketches, however, are important keys to understanding the full intent of Haraway’s ironic myth. The Manifesto calls on SF in a number of ways. First, and crucially, looking to SF becomes a way of foregrounding and talking about the mythic elements of technoscience. The Manifesto is centrally concerned with a reconstruction of socialist-feminist politics “in the belly of the monster” – a drive that requires a “theory and practice addressed to the social relations of science and technology, including crucially the systems of myth and meanings structuring our imaginations” (Haraway 1991a: 163). For Haraway, SF is a useful tool for foregrounding such “systems of myth;’ especially if we export our SF reading practices to science and see both as stories about science. The Greek tragedians were likewise criticized by Aristotle. In his Poetics, Aristotle does not just put forward an early version of Western craft (one closely tied to his philosophical project of the individual) but also puts down many of his contemporaries, tragedians for whom action is driven by the interference of the gods (in the form of coincidence) rather than from a character’s internal struggle. It is from Aristotle that Westerners get the cultural distaste for deus ex machina, which was more like the fashion of his time. Aristotle’s dissent went forward as the norm.

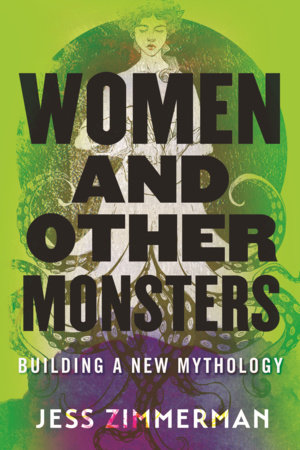

The Greek tragedians were likewise criticized by Aristotle. In his Poetics, Aristotle does not just put forward an early version of Western craft (one closely tied to his philosophical project of the individual) but also puts down many of his contemporaries, tragedians for whom action is driven by the interference of the gods (in the form of coincidence) rather than from a character’s internal struggle. It is from Aristotle that Westerners get the cultural distaste for deus ex machina, which was more like the fashion of his time. Aristotle’s dissent went forward as the norm. “Justice is not severed in The Eumenides, either. The trial is a nightmare, really. Orestes and Apollo argue that mothers aren’t really the parents of their children, just receptacles for a father’s seed. This convinces only some people, and the jury votes six to six. Then, Athena, casting the deciding vote, says flat out she only really cares about men, which means she considers Clytemnestra killing Agamemnon a worse offense than Orestes killing Clytemnestra. I like Robert Lowell’s translation because it doesn’t mince words: “I killed Clytemnestra. Why should I lie?” says Orestes. “The father not the mother is the parent,” says Apollo, who adds that the mother is only “a borrower, a nurse.” “I owe no loyalty to women. / In all things…I am a friend to man,” says Athena. “It can’t mean much if a woman, who has killed her husband is killed.” Orestes, in other words, is acquitted explicitly on the strength of disdain for women. It doesn’t matter if your reasons are good when you control the law.

“Justice is not severed in The Eumenides, either. The trial is a nightmare, really. Orestes and Apollo argue that mothers aren’t really the parents of their children, just receptacles for a father’s seed. This convinces only some people, and the jury votes six to six. Then, Athena, casting the deciding vote, says flat out she only really cares about men, which means she considers Clytemnestra killing Agamemnon a worse offense than Orestes killing Clytemnestra. I like Robert Lowell’s translation because it doesn’t mince words: “I killed Clytemnestra. Why should I lie?” says Orestes. “The father not the mother is the parent,” says Apollo, who adds that the mother is only “a borrower, a nurse.” “I owe no loyalty to women. / In all things…I am a friend to man,” says Athena. “It can’t mean much if a woman, who has killed her husband is killed.” Orestes, in other words, is acquitted explicitly on the strength of disdain for women. It doesn’t matter if your reasons are good when you control the law.