Tag: mythpunk

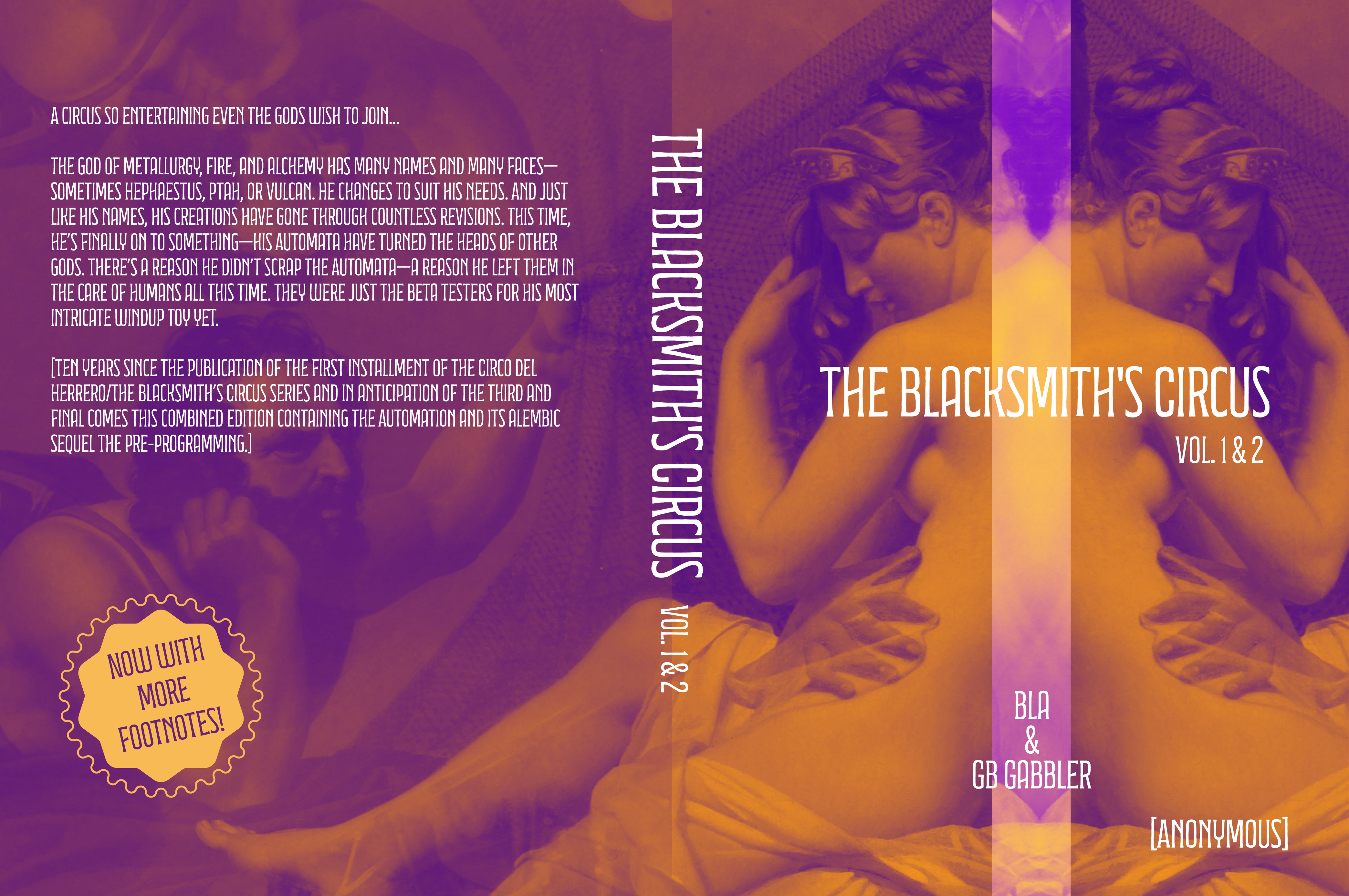

Now available for pre-order: The Blacksmith’s Circus Series Combined Volumes 1 & 2 edition

Celebrating 10 years since the publication of The Automation, comes a combined edition — married until their third arrives.

GABBLER RECOMMENDS: The Flowering Wand by Sophie Strand

Quotes from The Flowering Wand we liked:

“How can a monotheistic sky god rule the dirt, the fungi, the funky and sexy reality of embodied life if he is always hovering above it? How can he understand the millions of different stories that constitute an eco-system if he insists there is only one story and one god?

Monotheism is trapped by its attachment to a mythic monologue. Sky gods think sunshine, abstraction, and ascension are the answer to everything. But the problem with the sun is that if it isn’t tempered by darkness and rain and decay, it tends to create deserts instead of biodiverse ecosystems. We are ground people who have been worshiping sky stories not properly suited to our relational existence rooted in the land. Sporulated storm gods come from the ground, like us, so they understand our soil-fed, rain-sweetened existence. They bring the wisdom of the underworld and lift it into the sky, only to pour it back into the leaves, the grasses, the valleys, soaking back into the dirt from which they originally emerged. Sky gods encourage linear thinking. Spore gods teach us that everything is cyclical. Yes, sometimes we must ascend like a spore on the wind, but it is also important to descend back into our bodies and back into the earth.” – pg 13

Monotheism is trapped by its attachment to a mythic monologue. Sky gods think sunshine, abstraction, and ascension are the answer to everything. But the problem with the sun is that if it isn’t tempered by darkness and rain and decay, it tends to create deserts instead of biodiverse ecosystems. We are ground people who have been worshiping sky stories not properly suited to our relational existence rooted in the land. Sporulated storm gods come from the ground, like us, so they understand our soil-fed, rain-sweetened existence. They bring the wisdom of the underworld and lift it into the sky, only to pour it back into the leaves, the grasses, the valleys, soaking back into the dirt from which they originally emerged. Sky gods encourage linear thinking. Spore gods teach us that everything is cyclical. Yes, sometimes we must ascend like a spore on the wind, but it is also important to descend back into our bodies and back into the earth.” – pg 13

“Who is the monster of today’s legends? Today, we see a surfeit of media coverage devoted to weather and climate events. Has the biosphere become the monster? Every attempt to create weather- or climate-regulating technology, rather than adjusting and halting our won abysmal behaviors, posits Earth as monster and human kind as the ‘heroes’ who must control her and tame her and save her. Technonarcissists are the new Marduk. The new Theseus. They want the myth of progress to subsume the older (although newly investigated in the realms of quantum physics and glacial ice coring) chaos of emergent systems and biospheric intelligence. Earth doesn’t know best, our cultures insist. We know best. And we must progress ever onward toward greater control.” -pg 27

“The alternative to patriarchy and sky gods is not equal and opposite. It is not a patriarchy with a woman seated on a throne. The Sacred Masculine isn’t a horned warrior bowing down to his impassive empress. The divine, although it includes us, is mostly inhuman. Mutable. Mostly green. Often microscopic. And it is everything in between. Interstitial and relational. The light and the dark. Moonlight on moving water. The lunar bowl where we all mix and love and change.” -pg 33

“We are all increasingly strangers in the home of our own bodies: taught to ignore our subtle appetites and changing needs, taught to medicate symptoms rather than curiously inquiring into root causes. WE blast our microbiomes with antibiotics and spray away the natural pheromones that once carefully attuned us to choosing the right sexual mates. People with wombs are told that their menstruation needs to be treated with medication as if it were a disease. Food is seen as fuel, not sacrament. We treat our bodies like vehicles we can drive into the ground and then replace. We work hard to abstract our minds from our most sacred physical hearths.” -pg 34

“Emergent systems are characterized as systems that work as an assemblage of different entities. They represent the moment when chaos coalesces into synchronized, the relational patterns of a complexity that is utterly unpredictable. Examples are the murmurations of starlings, tornadoes, and fish schooling. Dionysus never shows up alone. He always has plants, leopards, lions, women, satyrs, or goats in tow. He is covered in snakes and vines. His whole presence shimmers and flickers: between genders, between species, between new and old, between known and unknown” -pg 39

“What was so shocking about the maenads? Euripides describes them with long loose hair, unbound and uncovered by a veil. They tamed wild animals and wore crowns fashioned of thrones and serpents. They were draped in fawn and leopard skins, symbolic attributes of the ancient Bronze Age nature goddess Cybele, and the wielded Dionysus’s fennel thyrsus. They danced and sang and rant through the groves. They drank wine and hunted wild animals with superhuman agility and strength. They ate raw flesh, a practice demonized by ‘civilized’ Rome and then the patriarchal sterility of modern academia. But it seems obvious that this rite of flesh eating is intimately related to the leopard and feline skins the women were wearing. They were enacting rites we see in shamanic practices worldwide: becoming the animals they worshipped, in habiting a wild mind, and participating intimately in animal appetites in order to obtain spiritual wisdom deeply rooted in the ecosystems. We delight in Ovid’s palatable poetic treatments of transmogrification. What is it about the maenad’s metamorphosis into lionesses that is so frightening?” – pg 63

“I’m not sure what the answer is, but I think by studying the invasive species in our local ecologies we can learn about subversive revolutionary tactics. What does it mean to digest a building? What if revolution involved sinking our hands into fresh loam and feeling for the threads of mycorrhizal fungi connecting plants and trees? What if, before we began to fight, we rooted back into our earth-based pleasure? We learn how to revolt when we make medicines from invasives and when we look curiously at what the land is doing, rather than immediately trying to ‘cure’ it or clean it up. What does it mean to transform a polluted landscape into a healthy forest? The landscape knows better than us and will show us if we look closely enough.” – pg 67

“The writing is clean and convincing. Society and purity are prized over darkness and uncertainty. Eloquence, that loaded word used to silence those who speak differently than the educated elite, is the hero’s gift, and a battle through linear time is his story.

Campbell’s theory of the monomyth was convincing enough that, although it faced much criticism, the hero’s journey has infiltrated the very pitch of our literature, our entertainment, and our psychological narratives. Even sperm have been transformed into little questing knights, journeying through the dark forest of the cervix until they can fertilize the egg, epitomized by Campbell’s idea of key episodes common to all hero narratives: ‘meeting the goddess’ and ‘woman as temptress.’

But the hero’s journey isn’t always the best fit. Contrary to popular belief, eggs are the dominant force when it comes to fertilization, actively choosing which sperm they will attract and allow implant. Now that we know better, what does the egg’s story sound like? What does it feel like to stand still and replete in your power to choose, not running off into the forest to slay dragons?” – pg 96

“The sight of a coppiced tree has always twinkled in my poet’s mind, reminding me that we are never limited to a binary, never stuck to one ‘tree’ or one course of action. Sometimes we need to cut down the tree of a monomythic idea in order to get to the more generative roots belowground that will spring into a polyphony of trunks aboveground. I’m not saying we need to throw out the hero’s journey. But we do need a biodiversity of stories. We need multiple sprouts from one trunk. We need stories that don’t center around human beings. And we need stories that do center around human beings. This is an invitation to cut back our ideas of linear progress and battle. To soften into the yellow sap of our stump for a moment. And then to being talking and singing and sprouting into as many stories as there are spores on the wind, bacteria in our gut, unsung loves in the forgotten corner of our feral hearts.

I am gifting all seventy-eight carts of the tarot to the masculine. That’s seventy-eight new nourishing archetypes…” pg 100

“Although I began my studies through the lens of the Divine Feminine, I find it no longer big enough for me. The opposite of patriarchy is not matriarchy. The opposite of civilization is not an idealized return to Paleolithic hunting and gathering. The opposite of a human is not an animal or a rock or a blade of grass. The opposite of our current predicament—climate collapse, social unrest, extinction, mass migrations, solastalgia, genocide—is, in fact, that disintegration of opposites altogether.

Everything is both. And more. And everything is penetratingly, painfully, wildly alive.” -pg 113

‘What if the dying, resurrecting god was not as natural a story as we’ve been led to believe? What if it didn’t so easily echo with ‘the return of spring’? There seems to be something deeply naïve about assuming that the god will resurrect. How many times can we gore a lover, send him to the underworld, castrate him, before he says, “Enough, already. I don’t want to come back.”

What I want to say, loudly, forcefully, is this: It is only initiation if you survive. And many do not survive. The way we live produces suffering, both our own and the suffering of others. It is only nature that our myths have sought to justify this suffering as sacred initiation or the only ground for rebirth and transformation. ON a personal scale we defend our addictions with stories. On a larger scale we defend our addiction to violence with violent mythologies.’ -pg 141

‘We are neither totally responsible for our current climatological crisis nor totally blameless. This is a call to mediate on the small cats of eucatastrophe that we can enact in our own lives. Noticing a possum, hit by a car, still alive and bringing it to a wildlife rehabilitator constitutes a eucatastrophe. Allowing a front lawn to run wild with milkweed and goldenrod and clover amounts to a eucatastrophe for struggling bee populations. Nothing that a friend isn’t returning calls and stopping by to check on them is a eucatastrophe. Protecting old-growth forests from logging is a eucatastrophe.’ -pg 147

‘Dionysus is a bull god. A grape god. A leopard god. The god of women. The god of androgyny and play. The god of ivy and invasive species… He is born three times. He is firstborn. He is various. And the Dionysian myths that survive accentuate this slipperiness. Dionysus disrupts our desire for a discrete, individual narrative that follows that arrow of time forward. He is immediately mycelial in his birth stories, branching off in many different directions from a variety of parents and locations…Semele is destroyed mid pregnancy by the cosmic power of Zeus. Despondent, Zeus gestates the zygote Dionysus in his own thigh.

Dionysus, then, is born of man and woman. He is a blend of genders from the start, and also of elements and cultures, so it is no surprise when legends tell us he is born with bull horns or turned into a baby goat.’ -pg 36-38

‘Dionysus was also popularly called Liber. In fact, this version of the vegetal god’s name is the root of our words for freedom and liberation and deliverance. Why, then, do we only think of Dionysus as a god of drunken foolishness? His worshippers very clearly saw him as a god of revolution and independence. Mythically, his arrivals signaled the inversion of social norms and the blooming of unfettered, uncivilized celebration, often conducted by society’s underdogs. This behavior isn’t just fermented ecstasy. This is spontaneous, unruly revolt.’

‘Put simply, maenads are women who know they aren’t different from the natural world. They are its poetic, feral creations. And thus, they are women reunited with older spiritual and ritualistic traditions that acknowledged their power. This is one of the reasons Dionysus was increasingly seen as a dangerous god by Roman authorities. I tis one of the main reasons he has been discredited as a drunken fool. Dionysus is not just the god of wine. He is the god of women. He comes to honor the maidens and the mothers and to reconnect them to a mythic mycelium that predates the rise of domination hierarchies during the Iron Age. He “crowns” them like he crowns Ariadne, returning to them their ecologically situated mystical authority that last fruited on Crete.’ – pg 63