‘With a few exceptions, in the myths as they have survived from antiquity, the inner workings and power sources of automata are not described but left to our imagination. In effect, this nontransparency renders the divinely crafted contrivances analogous to what we call “black box” technology, machines whose interior working are mysterious. Arthur C. Clarke’s famous dictum comes to mind: the more advanced the technology, the more it seems like magic. Ironically, in modern technolculture, most people are at a loss to explain how the appliances of their daily life, fro smartphones and laptops to automobiles, actually work, not to mention nuclear submarines or rockets. We know these are manufactured artifacts, designed by ingenious inventors and assembled in factories, but they might as well be magic. It is often remarked that human intelligence itself is kin of a black box. And we are now entering a new level of pervasive black box technology: machine learning soon will allow Artificial Intelligence entities to amass, select, and interpret massive sets of data to make decisions and act on their own, with no human oversight or understanding go the process… In a way, we will come full circle to the earliest myths about awesome, inscrutable artificial life and biotechne.’ – Adriene Mayor, “Made, Not Born.”

‘With a few exceptions, in the myths as they have survived from antiquity, the inner workings and power sources of automata are not described but left to our imagination. In effect, this nontransparency renders the divinely crafted contrivances analogous to what we call “black box” technology, machines whose interior working are mysterious. Arthur C. Clarke’s famous dictum comes to mind: the more advanced the technology, the more it seems like magic. Ironically, in modern technolculture, most people are at a loss to explain how the appliances of their daily life, fro smartphones and laptops to automobiles, actually work, not to mention nuclear submarines or rockets. We know these are manufactured artifacts, designed by ingenious inventors and assembled in factories, but they might as well be magic. It is often remarked that human intelligence itself is kin of a black box. And we are now entering a new level of pervasive black box technology: machine learning soon will allow Artificial Intelligence entities to amass, select, and interpret massive sets of data to make decisions and act on their own, with no human oversight or understanding go the process… In a way, we will come full circle to the earliest myths about awesome, inscrutable artificial life and biotechne.’ – Adriene Mayor, “Made, Not Born.”

The dream of building minds is an old one. How old? You may be surprised to learn that the ancient Greeks had myths about robots. In “Gods and Robots,” Stanford science historian Adrienne Mayor describes how, more than 2,500 years before the modern computer, people told tales of autonomous machines that could labor, entertain, kill and seduce.

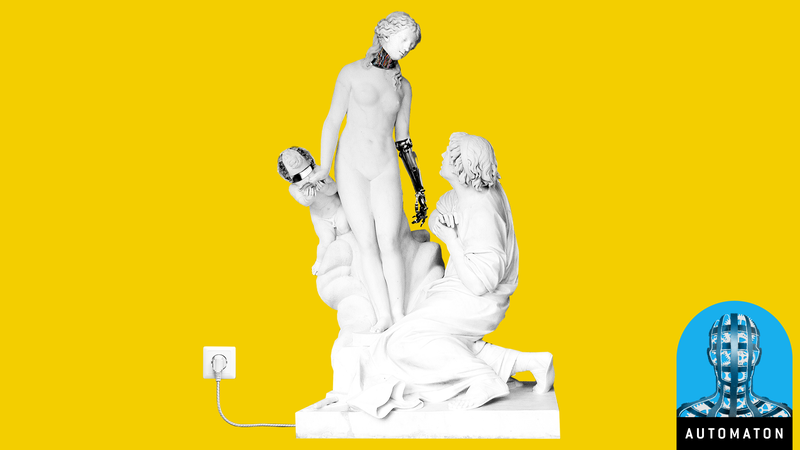

The dream of building minds is an old one. How old? You may be surprised to learn that the ancient Greeks had myths about robots. In “Gods and Robots,” Stanford science historian Adrienne Mayor describes how, more than 2,500 years before the modern computer, people told tales of autonomous machines that could labor, entertain, kill and seduce. Although the Pygmalion myth is often presented in modern times as a romantic love story, the tale is an unsettling description of one of the first female android sex partners in Western history. It is not clear that Pygmalion’s passive, nameless living doll possesses consciousness, a voice, or agency, despite her “blushes.” Has Aphrodite transformed the perfect female statue into a real live woman, with her own independent mind—or is she now “just a better simulation?” The statue is described as an idealized woman, more perfect than any real female. So Pygmalion’s replica “surpasses human limits,” much like the sex replicants in the Blade Runner films that are advertised as “more human than human.” Ovid, notably, does not describe her skin and body as feeling lifelike. Instead Ovid compares her flesh to wax that becomes warm, soft, and malleable the more it is handled—in his words, her body “becomes useful by being used.”

Although the Pygmalion myth is often presented in modern times as a romantic love story, the tale is an unsettling description of one of the first female android sex partners in Western history. It is not clear that Pygmalion’s passive, nameless living doll possesses consciousness, a voice, or agency, despite her “blushes.” Has Aphrodite transformed the perfect female statue into a real live woman, with her own independent mind—or is she now “just a better simulation?” The statue is described as an idealized woman, more perfect than any real female. So Pygmalion’s replica “surpasses human limits,” much like the sex replicants in the Blade Runner films that are advertised as “more human than human.” Ovid, notably, does not describe her skin and body as feeling lifelike. Instead Ovid compares her flesh to wax that becomes warm, soft, and malleable the more it is handled—in his words, her body “becomes useful by being used.”