“But the controversy also raises questions about another issue that touches directly upon writing: this is the way in which literature is coming to be embedded within a wider culture of public spectacles and performances. This process, which got under way almost imperceptibly, has now achieved a momentum where it seems to be overtaking, and indeed overwhelming, writing itself as the primary end of a life in letters.

A frequently heard argument in favour of book festivals is that they provide a venue for writers to meet the reading public. Although appealing, this argument is based on a flawed premise in that it assumes that attendance is equivalent to approbation. Books, by their very nature often give offence and create outrage, and this is bound to be especially so in circumstances where there are deep anxieties about how certain groups are perceived and represented. In democratic societies, those who are offended or outraged are within their rights to express their views so long as they refrain from violence and remain within certain limits. They are even entitled to resort to demonstrations, dharnas, occupations and the like; in circumstances where any arm of the government plays a role people are entitled also to press for the withdrawal of public funds or sponsorship (something like this has already happened in the US in relation to publicly-funded TV and radio channels). The equation is quite simple: to expand the points of direct contact between writers and the public is also to increase the leverage of the latter over the former.

Writers and readers have not always stared each other in the face. Until quite recently most writers shrank from the notion of publicly embracing their readership. I remember once being at an event with the American novelist William Gaddis: this was in the nineteen-nineties and he was in his seventies then. A major figure in American post-modernism Gaddis had been reared in a very different culture of writing: he would not sign copies or take questions from readers. He refused even to read aloud from his book. After much persuasion he agreed to sit silently in front of the audience while someone else read out passages from his work. When we talked about this afterwards he said quite categorically that he believed that books should have lives of their own and that writers could only diminish the autonomy and integrity of their work by inserting themselves between the reader and the text.”

[Via]

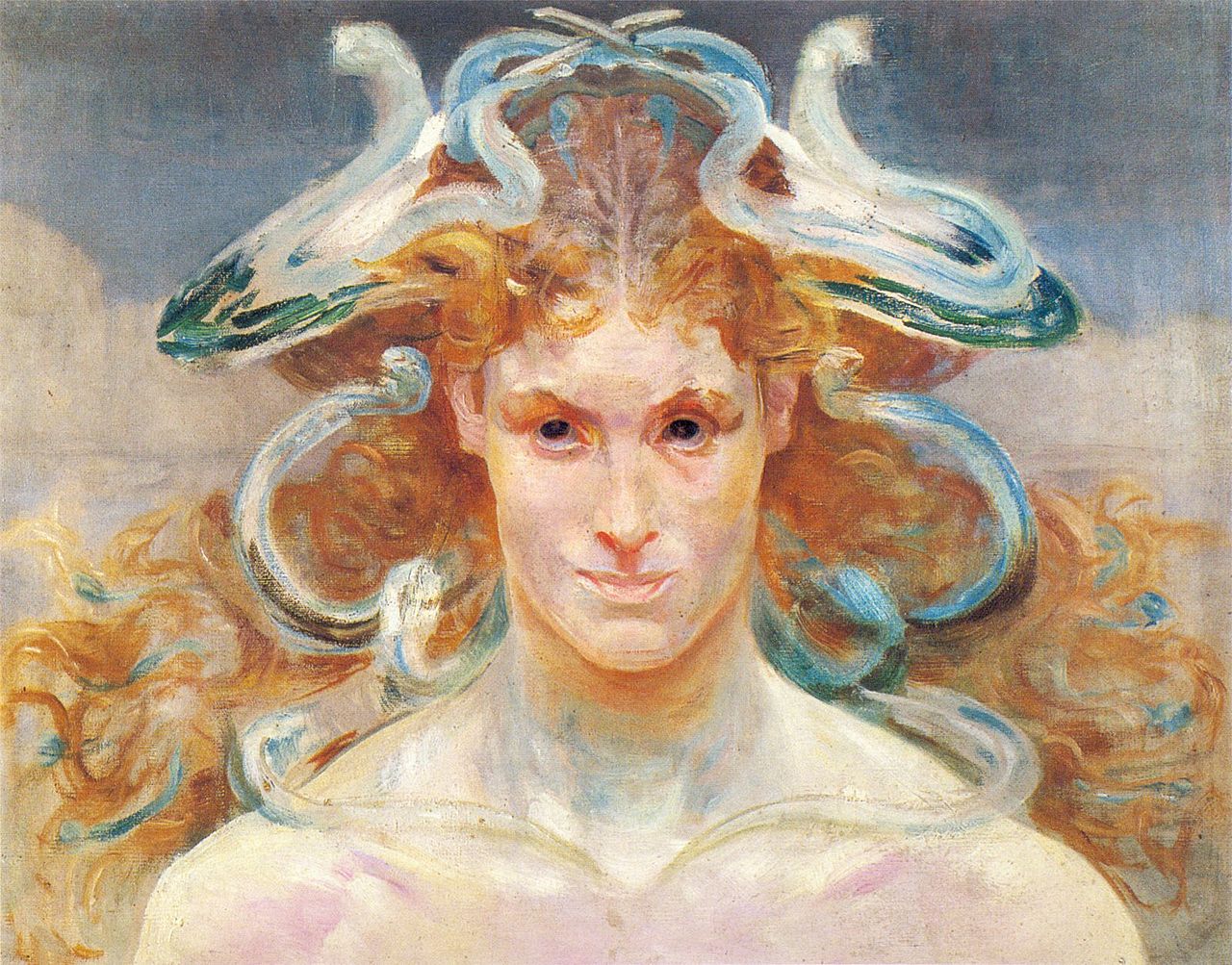

A ghost is the spirit of a dead person. An avatar is a digital twin of a living person. Neither is “real.” A haunted metaverse. Why not?

DC: Personally, it really blew my mind when I hit middle school and realized that the women D’Aulaires’ referred to as Zeus’s “many wives” were actually his mistresses, and not always consensually so. Did you have any moments of shock when you moved from D’Aulaires’ to Ovid and Homer?

DC: Personally, it really blew my mind when I hit middle school and realized that the women D’Aulaires’ referred to as Zeus’s “many wives” were actually his mistresses, and not always consensually so. Did you have any moments of shock when you moved from D’Aulaires’ to Ovid and Homer?