Apologies that this isn’t as timely as I’d have liked. I’ve been meaning to craft this post for a long while.

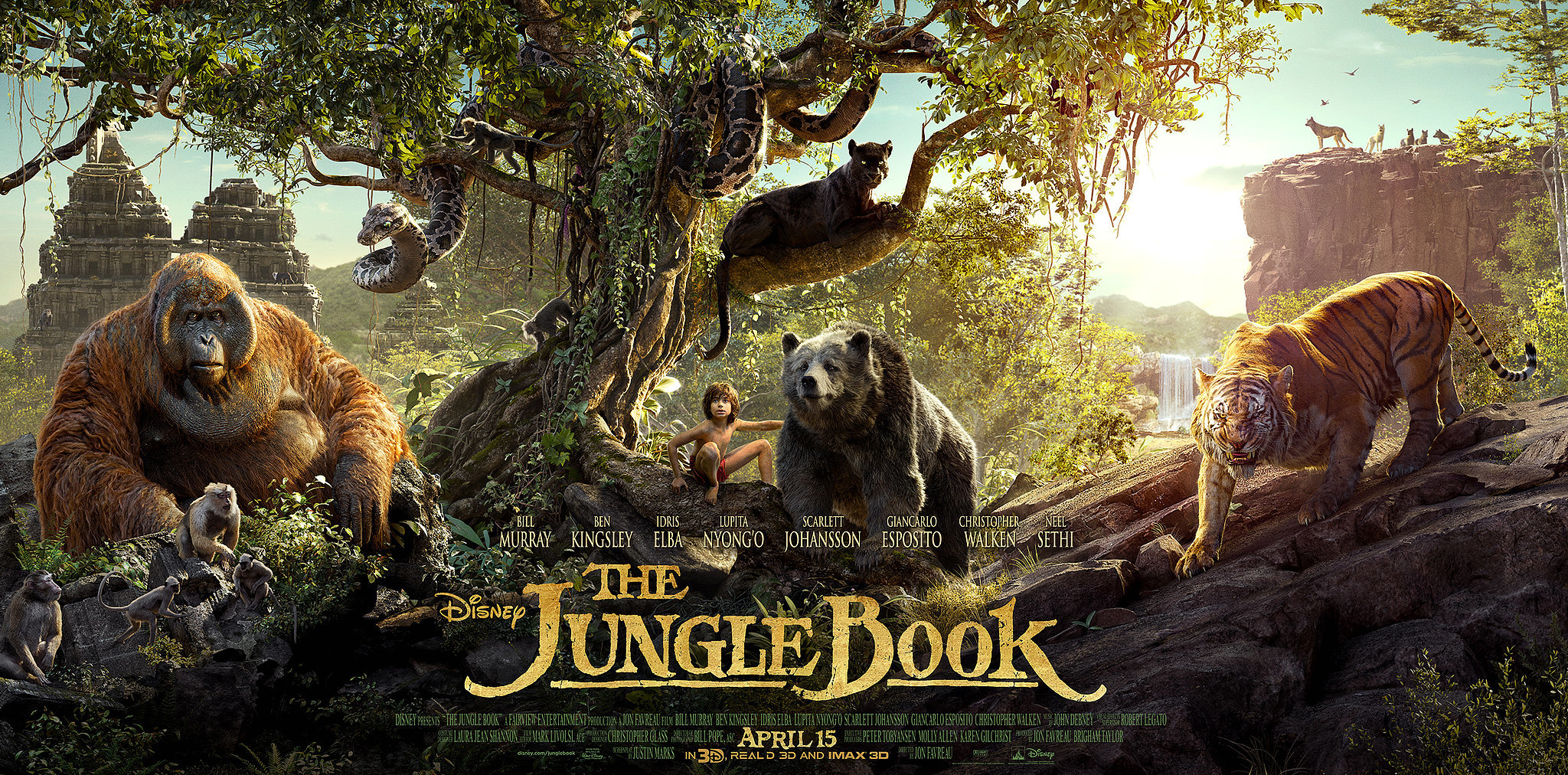

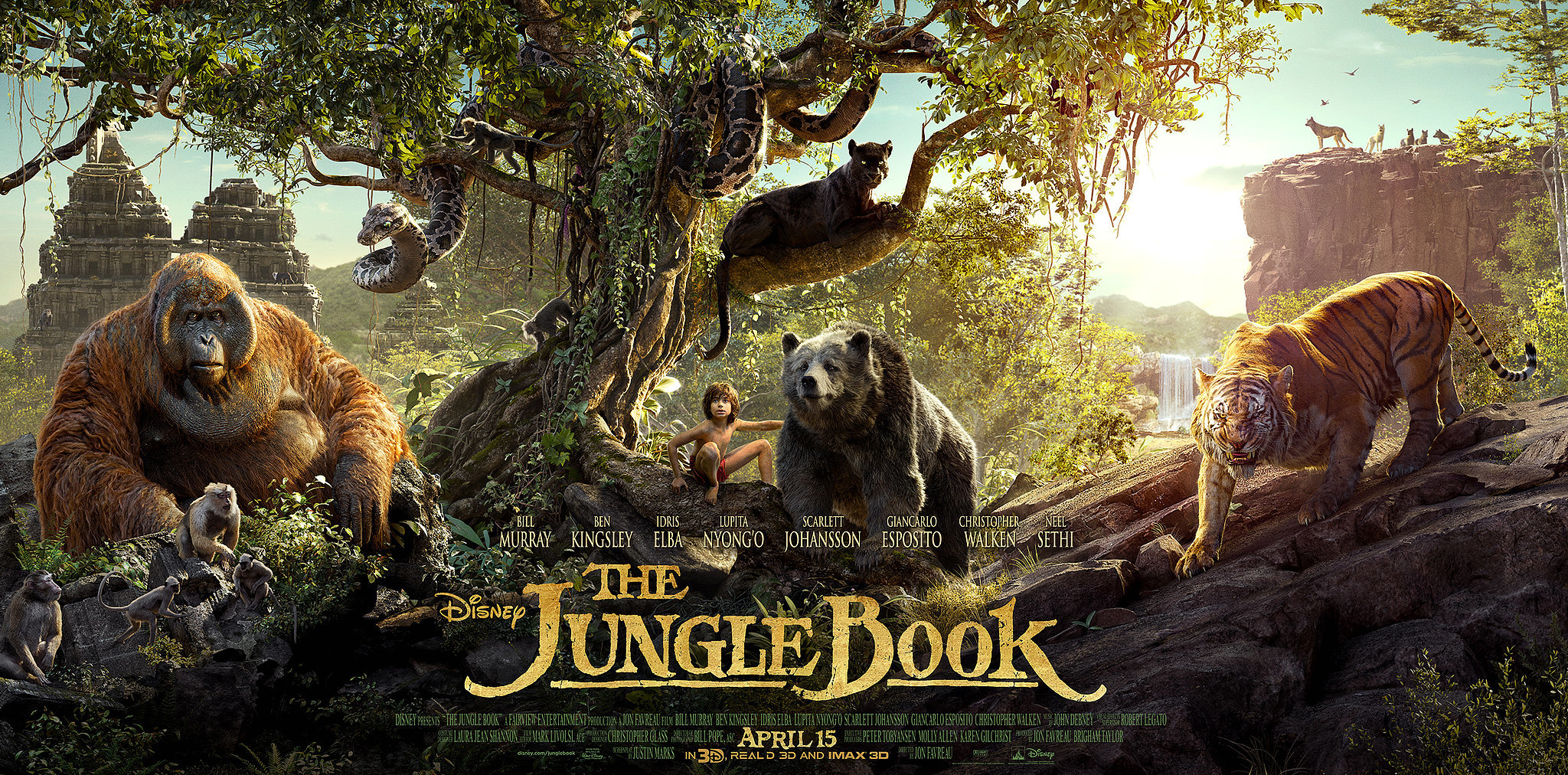

In a previous thought of mine, I dreaded the 2016 Disney adaptation of The Jungle Book–not just for colonial reasons, but for the blatant humans-are-better-than ____ (fill in the blank) mentality. HOWEVER…I was pleasantly surprised.

Before watching the movie, I thought nothing of the fact all animals were CGI in the film–no need for captive animal actors/animal abuse. I’ve even seen the director, Favreau, give an interview where he seems proud of the fact no animals (except human ones) were used, never mind the exotic animal ban.

Such a respectful approach leads to greater creativity and avoids mishaps like racist “Jungle Monkeys.”

King Louie, the orangutan made famous in the 1967 Disney adaptation of The Jungle Book, presents a problem. King Louie was not actually in Rudyard Kipling’s original story. This makes sense because Orangutans (two species in the Pongo genus) are native to southeastern Asia and not India. [Via]

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6341417/junglelouie.jpg)

In the 2016 film, I believe Louie calls himself “gigantopithecus” (at least in song), which is a long extinct form of ape. But hey, if a human boy can learn the animal languages of the jungle, then why can’t there be one last living gigantopithecus? I’m far more interested in the representation of said species than the believably.*

From here on out is SPOILER territory.

Unlike the animated film–thank the film gods–animals are treated with much more dignity:

But when the animals shut their mouths and run, climb, or fight, they’re marvelously convincing. And that becomes key in a movie that’s so much about the clash of animal wills and bodies, and about the rules — both instinctive and traditional — that guide their behavior. The 1967 animated versions of these characters also move with a liquid and believable animal sleekness, earned by careful study of real animals in the Disney studio. But they’re also softened and anthropomorphized cuddly cartoons. In the live-action version, the animal protagonists have visceral weight and impact, aided by tremendously effective sound design that makes every step or strike palpable. When Kaa the python (voiced by Scarlett Johansson) sinuously slithers along a straining tree, or the animal characters rip at each other with claws and fangs, the bodies feel convincingly, intimidatingly real…

The songs don’t particularly fit into this darker, wilder Jungle Book, which brutally kills off a beloved character, and climaxes in a bloody face-off that’s miles away from the Disney classic’s quiet, domestic ending. Favreau and Marks’ version is surprisingly daring in its use of violence, and its physical and emotional darkness. It’s also creative, occasionally in bizarre and colorful ways. The filmmakers build a strange and solemn cosmology around elephants. They re-envision Mowgli as a junior engineer, resourcefully building and using tools in ways that unnerve the jungle denizens. And they bring back Kipling’s murderous gravity, and the sense of danger and wonder that his writing brought to these stories. [Via]

In the film, the animals as well as Mowgli wrestle with what a “man-cub” turns into–and what that means for Mowgli and the Jungle dynamic. Someone else’s thoughts on that dynamic:

In his captivating tale of man-cub and beasts (originally published in 1894), Kipling delivers an account of a world both lethal and fascinating. In that world, we learn, there are packs we are born into and laws that have been devised to protect us; there are shifting alliances and adaptations that save us; there is danger but also care. Kipling’s fictional world is timeless, although for generations people have read The Jungle Book and comforted themselves by assuming (incorrectly) that their own times are far more civil, better educated, and more morally grounded.

…His animal “community” includes characters whose traits are familiarly human: a mother wolf prepared to fight to her death for a child who is not of her own body; Baloo the sleepy brown bear who has “no gift of words” but speaks the truth knowing that “learned wisdom” can protect the young; Bagheera the black panther who is a cunning, bold, and reckless creature who also knows how to listen to nature; Akela the pack leader who would save his wolf family shame by teaching them honor; Shere Khan, a Judas in the jungle, ready to betray anyone; and the gray apes who have no leader and no laws. Such types are as common among humans on the streets of any modern city as they are in Kipling’s nineteenth-century Indian jungle.

When Kipling places the gentlest of souls—a child—into this wild place, he introduces an implicit challenge to the Law of the Jungle. In trying to make sense of the jungle’s unspoken rules, the child, Mowgli, discovers his own creativity and natural curiosity—and naturally tests the rules. But he eventually realizes he needs the protection of those same sacred rules to survive.

And despite their anthropomorphized traits, the animals are still animals; Mowgli is different. When he prepares to leave the wolf pack for the first time to escape the marauding Shere Khan, Mowgli experiences a heartbreak that brings tears to his eyes, a human capacity unknown to his animal brothers. [Via]

I disagree with that last part immensely, but agree they are still animals. Their dignity and differences have not been taken away. Aaaand, if you want to talk about a “capacity unknown to his animal brothers” let’s focus solely on Mowgli’s engineering feats. The animals are often afraid of what tools he uses–because change and the unfamiliar are scary–HOWEVER, they are forced to acknowledge his contraptions and inventions ultimately help them, whether it’s getting honey for Baloo or trapping Shere Khan. There is symbiosis. (Also, “Gentlest of souls”? A human kid? Really? Human children are the worst kind of turd. Maybe you need to play with a few sloth babies to GET REAL).

He struggles with his love for the mother who has raised and protected him and worries greatly that he will be forgotten by his parents. The Law of the Jungle demands many things of its inhabitants, (even that some, like Mowgli, leave the jungle) but it also provides a foundation for these bonds. [Via]

HOWEVER, to the greatest surprise of all, in the end of the the 2016 live action adaptation Mowgli does not decide to segregate to his “kind”–and definitely not out of superiority or sexualized reasons. He does not go back to man. He stays in the jungle with his animal family. He and animals co-exist.

Whether the film’s message is intentional or not, our relationship with the animal kingdom is a “bare necessity” of life.

*Wanting to say something snarky here about anthropomorphism but can’t because it would spoil our own book…

Written by BLA and edited by GBG (thus the footnote).

[“BLA and GB Gabbler” (really just a pen name – singular) are the Editor and Narrator behind THE AUTOMATION, vol. 1 of the Circo del Herrero series. They are on facebook, twitter, tumblr, goodreads, and Vulcan’s shit list.]

B&N | Amazon | Etc.

B&N | Amazon | Etc.

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6341417/junglelouie.jpg)